2018 is the centenary of the armistice. It’s also one hundred years since women were given the vote.

National Trust houses are few and far between where I live but Killerton, near Cullompton in Devon, is a favourite. This autumn it played host to an exhibition, Women and Power: The Struggle for Suffrage. As it ends this month, I was just in time when I visited yesterday.

Killerton houses a costume collection and while downstairs featured campaign games in the music room and quotations representing both sides of the debate in the dining room, upstairs investigated the role fashion took in the movement. The glass screen protecting the costumes on display has been given the illusion of being broken. Breaking windows was often used by the militant suffragettes in an effort to get their message across.

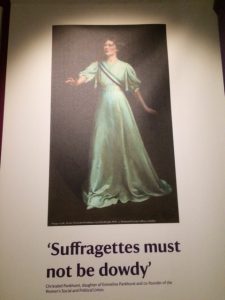

As a rebuttal to those who mocked the suffragettes and accused them of being masculine, Christabel Pankhurst exhorted supporters to take pride in their appearance and not be ‘dowdy.’

Colours were highly symbolic: purple being the colour of royalty and dignity, white standing for purity and green being the colour of hope. Allegiance to the cause was shown by wearing sashes, hat decorations, ties and badges – all in the three colours of the suffrage movement.

There were also sub-divisions within the suffrage movement. The suffragists had been campaigning within the law for some time, slowly gaining momentum. It was too gradual for the militant suffragettes, led by the charismatic Emmeline Pankhurst. Her ‘Deeds not Words’ slogan and crusade of violence tried to force through change. Demonstrations, breaking windows, arson, even bombings, were all weapons in their campaign.

Differences divided families. The Acland women, who lived at Killerton, clashed. Eleanor Acland, a leading suffrage campaigner, was in strident opposition to her anti-suffrage aunt Gertrude. She also advocated peaceful means of protest, putting her into conflict, in turn, with the more extreme suffragettes.

Many women felt as Gertrude Acland did, that women did not need the vote. Surprising anti-suffrage supporters included George Eliot, Florence Nightingale and founder of the National Trust, Octavia Hill. Women such as these perhaps felt they already had influence themselves, or through their husbands. They too, could demonstrate their political views with dress.

The outbreak of war brought an end to all campaigning and, eventually, in 1918, to the vote being awarded to all men over 21 and to women, who met certain property requirements and who were over 30. The working class women, who had served their own war on trains and busses, ‘coke heaving,’ working in shipyards and risking their health and life in munitions factories had to wait until 1928.

The National Trust curated the exhibition with its usual flair. It was a glorious October day when I visited and Killerton was busy with families on half term. A beautiful day for a sombre and thought-provoking exhibition.

Love,

Georgia x